Prior to our son’s possible exposure to measles, I did not think about how my choice to vaccinate my children affected anyone but my own child. But when measles was brought close to my son Ben, my insulated view was shattered.

Prior to our son’s possible exposure to measles, I did not think about how my choice to vaccinate my children affected anyone but my own child. But when measles was brought close to my son Ben, my insulated view was shattered.

My decision about vaccination could impact anyone my children would come in contact with for their entire lives. If one of my children was infected with a vaccine-preventable illness, he could unknowingly pass this illness on. While a person with an average immune system may be able to fight off the illness, a person with a weakened immune system might not. I now recognize one way our family can protect the greater community. Here’s the story of how we came to realize that vaccines are about more than just our family.

In 2010 our then two-year-old son, Ben, was diagnosed with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL). His diagnosis meant he would spend more than three years being treated with chemotherapies and steroids. During this time, and for many months afterwards, his immune system was compromised. Every minor illness had the potential to balloon into a more complicated condition requiring additional treatments.

In March 2011, Ben received a routine spinal tap during which spinal fluid was removed and chemotherapy was injected in his spine. Days after his treatment we were informed that a child in the same unit had been diagnosed with measles. Ben could have breathed air containing the measles virus.

Yes, Ben had received the first shot in the Measles, Mumps, Rubella (MMR) vaccine series, but he was too young to have received his second dose and wouldn’t be able to for months after finishing treatment. Despite having received MMR, his therapy would suppress his immune system and essentially eliminate any immunity he had to measles, so it would be as if he were never immunized. Because of his weak immune system, doctors classified Ben as being at high-risk should he contract measles. Measles is particularly dangerous to those with weak immune systems, including infants, because it can turn into pneumonia and bacterial infections. This possibility was one of my worst fears–second only to hearing that Ben was no longer in remission.

After Ben’s potential exposure, he received nitrous oxide while being given shots to boost his immune system. Seeing four nurses work together to give him one round of shots and then get ready for the next round was dreadful for me as a mother. I looked into Ben’s innocent eyes as he was in “dreamy land” and could barely speak without crying. How could anyone ask Ben to fight more than leukemia? It is more than enough to ask a young child to fight leukemia–but to ask him to fight a vaccine-preventable disease on top of it? It is unconscionable.

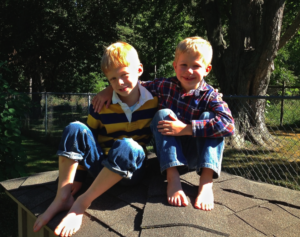

Our night ended with Ben’s legs hurting so much he couldn’t walk. My world had once again fallen apart. I shed many tears that day, and in the days that followed. I ate and slept very little. My mind was constantly on that measles diagnosis. How could I sleep not knowing if Ben would wake up with a rash, fever, or any ailment that could be a symptom of measles? I checked on him every night and cherished the moments when he was sleeping soundly. Every day was a blur; I was just trying to function. Our two kids played and talked around me, but I didn’t hear much that was said. Doctors had told us that Ben had to be quarantined for twenty-one days, because of fears that he could be harboring the measles virus and could transmit the illness to others in the community who were unable to be vaccinated–or those children whose parents intentionally left them unvaccinated.

Our night ended with Ben’s legs hurting so much he couldn’t walk. My world had once again fallen apart. I shed many tears that day, and in the days that followed. I ate and slept very little. My mind was constantly on that measles diagnosis. How could I sleep not knowing if Ben would wake up with a rash, fever, or any ailment that could be a symptom of measles? I checked on him every night and cherished the moments when he was sleeping soundly. Every day was a blur; I was just trying to function. Our two kids played and talked around me, but I didn’t hear much that was said. Doctors had told us that Ben had to be quarantined for twenty-one days, because of fears that he could be harboring the measles virus and could transmit the illness to others in the community who were unable to be vaccinated–or those children whose parents intentionally left them unvaccinated.

It was hard to wrap my mind around the idea that despite our efforts to keep Ben away from sick kids, now he was the “risk” to the community–because of someone’s choice to take a risk on their child’s behalf. We were now forced to further alter Ben’s life.

On day 19 of our isolation, a rash developed on Ben’s cheeks. Within hours, Ben’s doctor called and said the department of health was concerned the rash could be measles and that Ben needed a measles test. The next day, a nurse took samples. At this point my anxiety should have peaked, but I admit I didn’t have much anxiety left. The hours went by with no answer. Was our life about to change dramatically for a second time? About thirty-three hours after the test, a nurse called to tell us that Ben tested negative. He did not have measles.

As you think about vaccinating your child, please keep in mind how an unvaccinated child can impact other children, particularly infants and those children who are fighting for their lives. Our son has already fought leukemia for three years of his life, a reality that has changed everything. I would never want him to also become a victim of a disease that should not even be in my community. Vaccines are safe and they save lives. By choosing vaccination, you will be protecting your child–and mine.

Laura Bredesen lives with her husband, her two children, and her two dogs outside of Minneapolis, Minnesota.

If you enjoyed this post, become a Voices for Vaccines member today.

Editor’s Note: Measles was officially eliminated from the United States in 2000. In March 2011, measles was brought back to Minnesota by an unvaccinated child who had traveled to Kenya, where measles is endemic. In addition to patients and providers in the hospital providing care to the child, workers and children in a daycare and individuals in two homeless shelters were exposed to measles. The resulting outbreak was responsible for 21 cases of measles, many of which required hospitalization.

The source of this outbreak is known. Seeing an opportunity to exploit fear of autism in one community, anti-vaccine groups worked to convince parents not to vaccinate based on the long-debunked theory connecting vaccines and autism. These same groups brought in Andrew Wakefield during this outbreak to bolster doubts about immunization. Amidst this anti-vaccine campaign, children like Ben were endangered.