by Noah Louis-Ferdinand

In February of 2022, COVID feels a bit abstract. It’s certainly not gone: we all saw the huge spike that was Omicron. But in a relative sense it feels diminished.

What makes the difference? Well, we should talk about what actually happened last month.

As the year turned, COVID hospitalizations got as bad as they’ve ever been. We knew from huge spikes in other countries that this surge was coming, so Americans were urged to get vaccinated and boosted to keep the system working. And while a fair number of people did so, it wasn’t enough.

January came. Hospitals filled up. And…

And what? It’s not like most of us were severely affected by this spike. For most people, it happened in the background. But only because the brunt of COVID now falls on those in the healthcare system, which is often too much for them to handle. To learn more about the effects of the surge, I wrote to doctors from six different hospitals to get a sense of how they’re doing.

They were honest. “It’s just a grind,” said ER doc Seth Trueger, “we have a 9/11 of deaths every two days, and the burden on the healthcare system is still massive.” Since his making this comment, The U.S. has reached 3,000 deaths every day. Sabrina Vineberg, a pediatric hospitalist, felt unheard: “This was preventable, and we’ve been telling you what to do for over a year and yet you didn’t do it.”

These doctors are struggling behind the scenes. It’s tempting to think the problem is overblown, but the simple fact is that hospitals never get this full. The resulting strain is dangerous for patients, which other writers have covered extensively. What I would highlight is what the problem says about how we view hospitals.

We are asking the people in them to make a sacrifice. Medical professionals are employees, but when their burden goes way up, we’ve gone beyond a fair exchange. They’ve been telling us in plain language how hard working in a hospital is right now. American society would be crushed by the coronavirus if there weren’t an element of service here.

“Everyone I know in health care is dead tired,” says John Ross, a hospitalist at Brigham and Women’s. Still he notes: “I am always grateful for the opportunity to take care of patients, including unvaccinated ones.”

As kind as that is, no human being can run on intent alone. We have to give people the chance to feel like they’re doing their job well. Those I wrote to perceived a sense of defeat in their colleagues. Frank Han, a hospital cardiologist, noted the rampant “burnout, professional dissatisfaction, and resignations.”

We’ve heard this before, and perhaps one too many times. Because now we no longer seem as invested in the hospital situation, which is understandable if ironic. Healthcare workers have been fighting the virus for 680+ days. They ought to be the most worn out. Seth said he felt like “the light at the end of the tunnel isn’t getting any closer.”

He was right when he said that in mid-January. At the same time, we as a society have moved out of the tunnel. And depending on how COVID affects us in the future, the divide will continue to be material. We shouldn’t leave hospitals like this.

Obviously, surges affect care. Strain on one part of the system limits others, as adolescent medicine physician Nicole Cifra put it: “None of us practices in complete isolation.” But more to the point, ours is a culture that tells itself that we value health professionals. Americans say being a doctor is the most prestigious career in society. We claim we would trust a nurse over just about anyone.

Of course, the honest measure of respect is how it is received. And a lot of healthcare workers feel like what they say and do has been devalued. “As a whole we’re pretty dedicated to medicine,” wrote Frank Han. “But when the patients who trust you to discuss cardiology with them do not trust your judgment on COVID…this can get intensely demoralizing.”

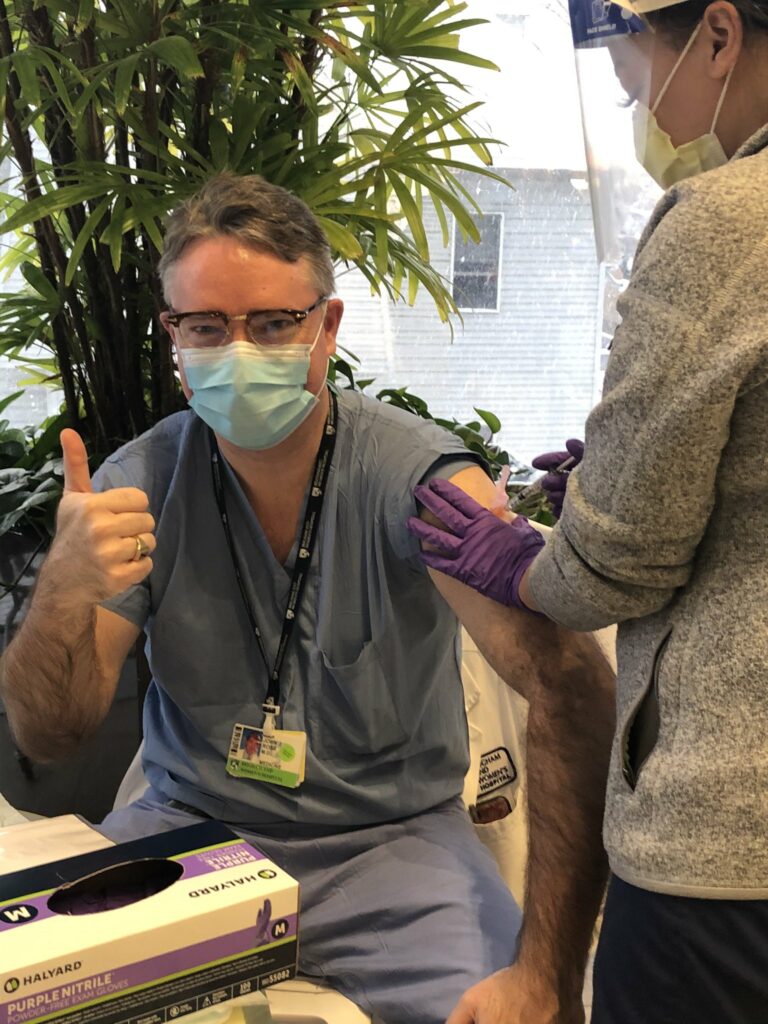

We know working under duress is itself bad for mental health. So in light of this fourth wave, we need to at least give healthcare workers our trust. The simple way to do that is to honor their most basic ask: get vaccinated.

If you still don’t feel great about it, I get that. I personally had no plans to get vaccinated until the nurses where I used to work talked me into it. But the more I get to know these people, the more I realize they need us to do our part so they can do their jobs. Trust is a two-way street.

I asked Wes Ely, an ICU doc, about our unwillingness to prevent COVID. If it was fair. “I don’t look at any one person and let it jade my care or love of that person. They all have their background reasons,” he replied. “I just try to meet them where they are.”

Let’s meet doctors where they are. Vaccinating is a small but essential act of reciprocity in a world where COVID is here to stay.

Noah Louis-Ferdinand is the Communications Coordinator at Voices for Vaccines.