by Erica Finklestein-Parker

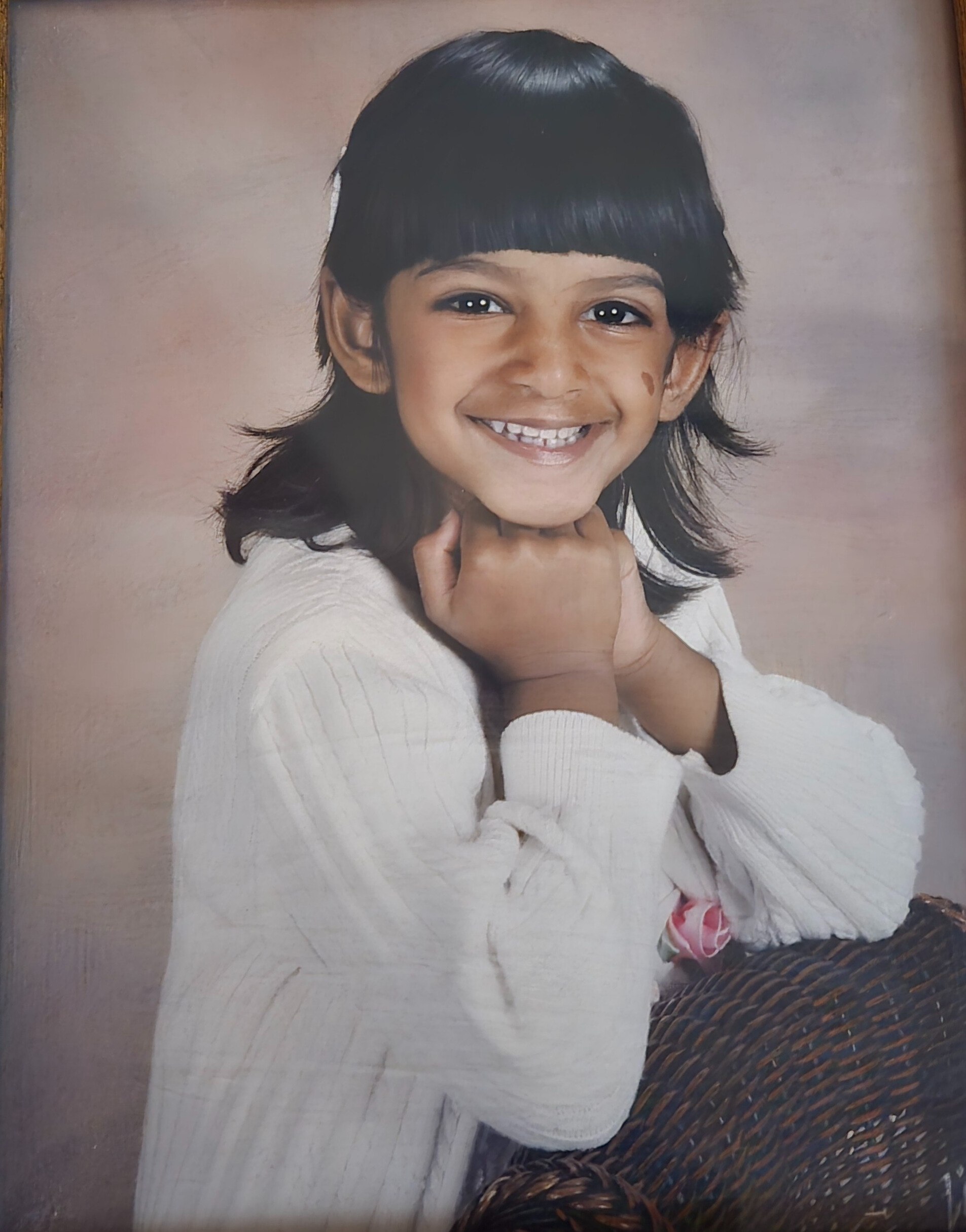

Emmalee Madeline Snehal Parker came home to us when she was 2 and ½ years old, in 2005, from an orphanage in India. She weighed 17 pounds. When you have a child who’s that age and weighs so little it’s hard to even find clothing. But Emmalee was 17 pounds of pure spitfire.

She was very friendly, and she loved climbing, running, and trying new sports. She loved being girly, all things pink and frilly. She went to a Jewish summer camp, and when she got off the bus every day, she would barrel down the hill, hug one of the rabbis at the knees, and almost knock him over, just to say good morning!

We would go down from our home in Littlestown, Pennsylvania, to Frederick for synagogue, where they had a playground. She’d look and see kids there, her eyes getting big, and she’d say “Friends!” She didn’t know who they were, but to her they were friends.

Emmalee had a really good life with us while she was here. And then in August of 2010, everything started to change.

The First Signs of SSPE

I had just gotten Emmy a new pair of shoes, and she was tripping and falling as she walked. I asked, “Emmy, are the shoes too big for you? Is that what’s wrong?”

She said, “Yeah, I guess.”

That wasn’t what was wrong. The next day, she started slumping to one side in her chair. She couldn’t keep her head up properly. I asked, “Emmy, why are you leaning to one side?”

She just said, “I don’t know.”

I obviously had no idea what was going on, but I sent emails to people I knew. One of my cousins is a pediatrician and researcher at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. She told me, “Pack a bag, get up here fast. I will let the neurological team know you’re coming to the ER.”

We got to the emergency room and, how life works with so many ironies, the first doctor who saw her was from India. I told him about the neurological symptoms Emmalee was having, and his face changed colors. The next thing he said to me was, “This child had measles. When did she have measles?” He immediately knew what was wrong, but didn’t have the test results to prove it yet.

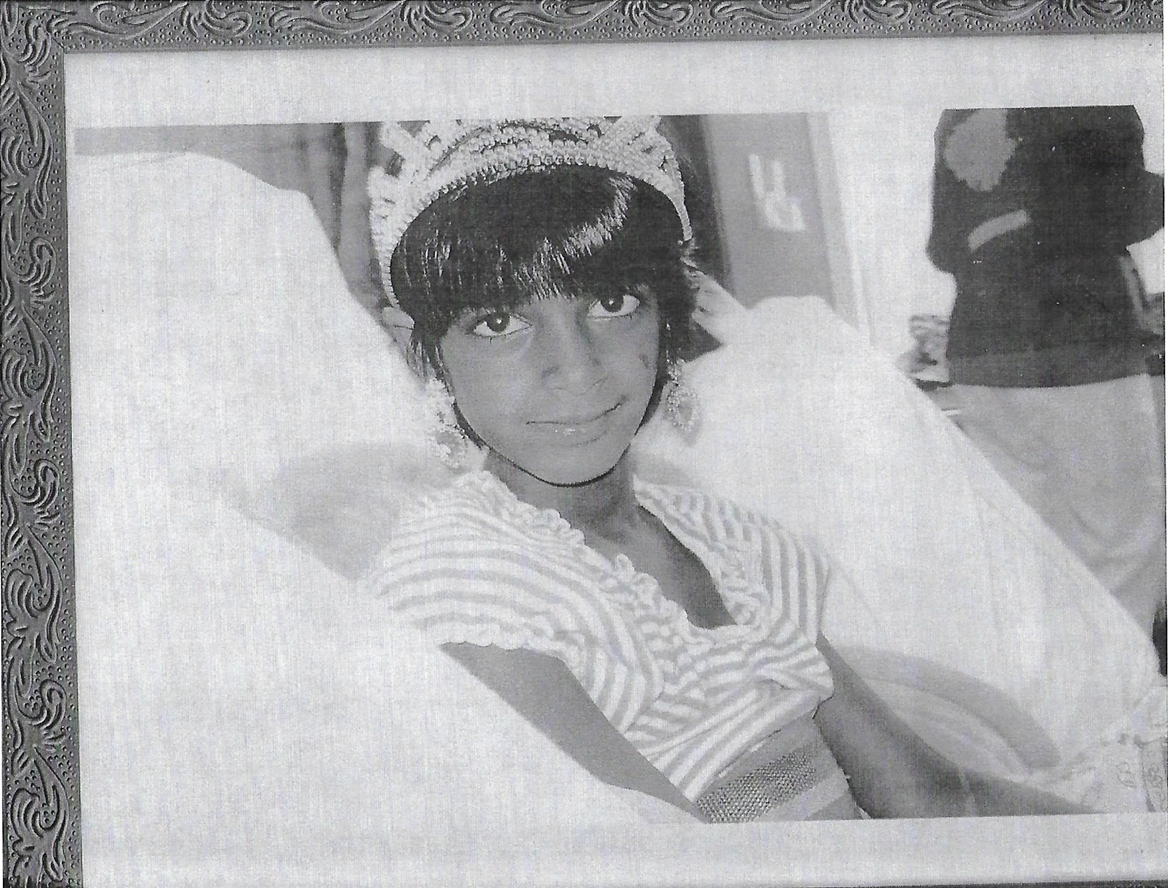

Emmalee wasn’t aware that anything serious was going on. One of the days we waited in the hospital, my mom brought Emmalee some princess jewelry, a tiara, and my earrings and bracelets. She was so proud of herself as she shook her head around, and the earrings dangled. She asked, “Mom do I look beautiful?”

“You do look beautiful.”

“These earrings hurt a lot. Can I take them off?”

“Yes, you should take them off.”

After a couple of days and some diagnostic testing, we were told that Emmalee had subacute sclerosing panencephalitis or SSPE.

They gave us the diagnosis in a room full of doctors and researchers. They knew so little about the condition that they had to print out decades-old internet pages from NIH. They handed them to me and said, “Here. This is all we know about SSPE.”

What we knew then was that it was an incurable complication of measles, where instead of clearing up, it gets into your spinal fluid and then goes into your brain. And we knew Emmalee would have worsening symptoms and almost certainly die.

How SSPE Progresses

My mom, my husband, and I came home, and we were all distraught. I didn’t know what to do. Being the person that I am, I started googling and found the world expert in SSPE. I called the hospital in Turkey where she worked, and she contacted my doctors to recommend a drug called interferon and another that wasn’t available in the US. So while my child was having trouble moving, walking, and eventually remembering, I was googling and making calls overseas to get medication that wasn’t on our FDA list.

The SSPE expert told us that she hadn’t had great results with the treatment, but sometimes you get lucky. We didn’t.

Emmalee hated the interferon injections. They had to go into her stomach, and it was horrible to give them to her. She would just become violent because she was so scared and upset. As things progressed, she had to wear an occupational therapy belt we could pull her up by because she kept falling constantly.

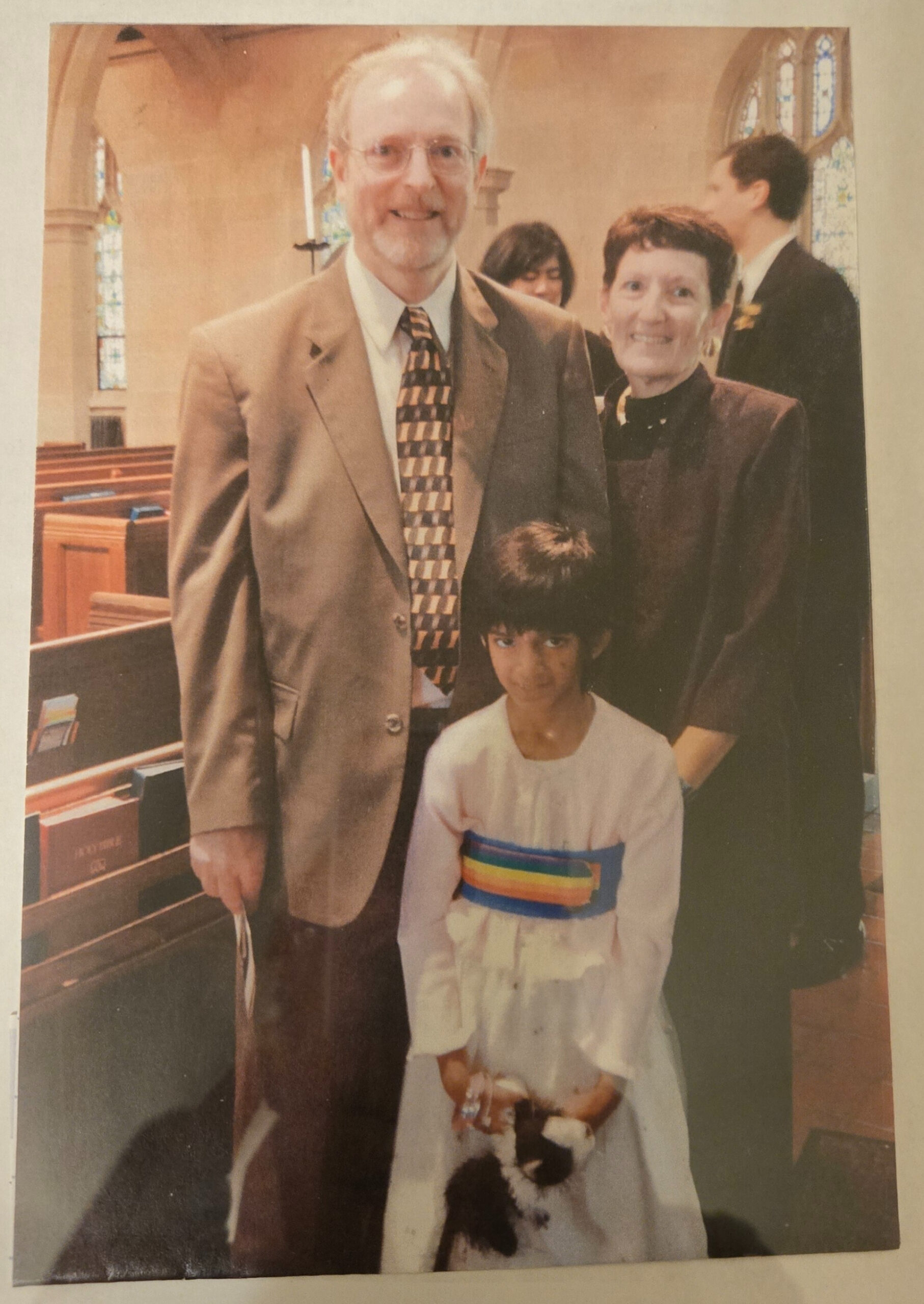

Not long before she passed, we were invited to a friend’s wedding. I got Emmy a beautiful white dress, putting the colorful therapy belt around her waist. While we were at the wedding, she lost the use of her legs and went down on the floor. I was scared to death. But then she got up and did a little twirl, saying, “Ta-da!”

I said, “Way to go, Emmalee!”

That day, I remember talking to the wedding photographer. I said to him, “Our daughter is really sick. Could you take a picture of us as a family, because I don’t think we’re going to get the chance to do any more portraits?” And they did, which was nice of them.

The doctors had told us about the falling. What we didn’t know was that she would lose her memory and forget who we were. Or that she would hallucinate. I remember one time coming home from the hospital, Emmy started screaming that there were witches flying by our window. And we turned around and went back, and I mean, I was hysterical.

At one point, as her issues got more and more severe, I went to talk to a room full of Emmalee’s teachers, and this is one of the hardest things in my life I’ve had to do. I told them, “My child’s not going to make it through the grade. But I want to thank you for everything that you’ve done, and she loves you.”

On the last trip to the hospital, Emmalee was screaming and so confused. She didn’t recognize our house. She looked at me, and she held my hand, but she didn’t know who I was. While there, Emmalee had these horrible, horrible seizures, which medications couldn’t stop. They essentially caused brain death, and she fell into a coma.

We brought her home in a van to do hospice. People expected us to rent an ambulance, and it was like, my child’s in a coma. She’s going home in a van.

I called friends and explained to them what was going on. So they got everything ready. We did hospice for our daughter in our bedroom for a couple of weeks. And that’s where she left us.

How We Coped

I cried a lot in the time afterward. My husband and I tried several therapy groups, but the way other parent’s children had passed wasn’t the same, so it didn’t fit for us. We just started meeting with our local pastor one-on-one, which was more helpful.

It’s one of those things where you continue with your life. But somehow you always feel like you’re watching a movie, like you’re on the outside. The people looking at you, you just look normal to them. But when you look in the mirror you almost see your soul through your eyes.

I wouldn’t say it gets easier. It just gets rolled into your experience, dulled. The one thing my pastor told me that I couldn’t accept for a while was that you don’t get over the pain. You walk beside it.

After Emmy passed, we got a call from her teacher, and she said, “The kids need closure. They love Emmy, and they need to know how you’re doing.” I thought, I don’t know if I can do this. But my husband and I went to the school, and the kids had made a mobile. Each piece of the mobile had a laminated memory, something about Emmalee.

Kids have a different way of dealing with things than adults. Where we feel utter sadness, they are able to be sad but happy about a memory at the same time. They remember things more colorfully, and more vividly. So that was wonderful.

Emmy's Hope to Prevent SSPE

It was a year after Emmalee passed before I could really function enough to start advocating. We started a nonprofit called Emmy’s Hope and that gave me a new lease. We did vaccine education at schools and community groups. We had a lot of contact with reporters and TV stations trying to get the word out.

Vaccine-preventable deaths should not happen. You don’t want this to happen to your child, your neighbor’s kid, or anybody else. Emmalee had a good life with us while she was here. But nobody should have to do hospice for their child. It’s just so unfair.

Even if your kid doesn’t end up with SSPE, they could go deaf, or have normal encephalitis and brain damage. It’s not worth taking a risk with your child’s life. If that kid turns around when they’re older and asks, “Why didn’t you get me vaccinated?” What is your answer going to be?

Erica Finkelstein-Parker and Brian Parker are the very proud parents of Emmalee and her brother and sister from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djino and Benedicte Mukala Parker. They live in Littlestown, PA. While Djino and Bene never met Emmalee, they have seen her pictures and heard her stories. They know what a spirit she was. Their family continues to advocate and tell their story to people to educate about the efficacy of vaccines.

Erica’s story, like all others on this blog, was a voluntary submission. If you want to help make a difference, submit your own post by emailing us through our contact form. We depend on real people like you sharing experience to protect others from misinformation.