by Monique Hopgood-Willis

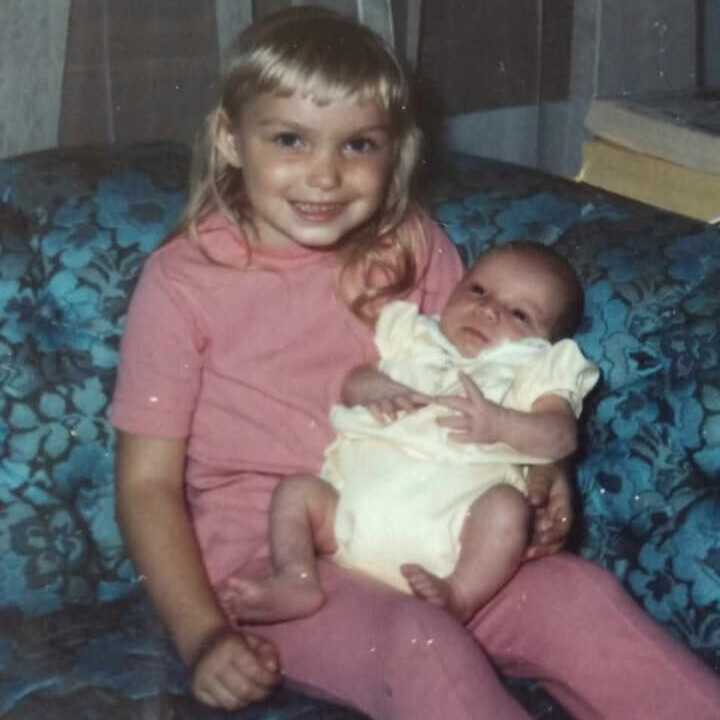

When I was 2 ½ years old, back in 1997, I got meningitis. At that time, the meningitis vaccine wasn’t available yet—it came out later, around 1999. My mom noticed something was wrong because I was super irritable, not acting like myself. She said she could just tell something was off. I had a rash on my leg, a symptom of my pneumococcal meningitis (though we didn’t know then). So my mom took me to the doctor. But the pediatrician said nothing was wrong, told her to give me Motrin, and sent us home.

The next day, while my dad was home with me, I started having spasms in my sleep. They weren’t full seizures but more like jerking movements. My dad noticed something wasn’t right and called my mom. They rushed me to the emergency room, and after a spinal tap, the doctors found out I had meningitis. I slipped into a coma, and the doctors told my parents that if I woke up—which they didn’t think I would—I’d probably never walk again or have a normal life.

I did wake up. And while I had to do physical therapy and relearn to walk and other things, I was all right. It was a thing of, “You had this disease called meningitis. God healed you. You’re a miracle.” And that was that.

The Hidden Challenges of Living with Epilepsy After Meningitis

But growing up, I didn’t feel like a miracle. I was clumsy and would trip over things. It took me forever to figure out the hand-eye coordination to button my school uniform. By the time I got to middle school, teachers noticed I would sometimes zone out. At first, they thought I was daydreaming, but it turned out I was having absence seizures. Around 7th and 8th grade, I started having full tonic-clonic seizures, but they would come and go, so doctors wouldn’t officially diagnose me with epilepsy. They just said it was a lingering symptom of meningitis.

They’d go away for about two years, and then come back again. When I was 16, I had a seizure during the ACT in front of a bunch of my classmates. I started getting the wrong kind of attention, with 16 and 17-year-olds looking at me like I was weird for the rest of my teenage life.

At 18, my boyfriend and I eloped. He noticed something was wrong and said to me, “You’re having a lot of seizures. We need to get you on some kind of medication, and get some idea of what’s going on.” My mom had given me all my medical records when he and I moved to Atlanta, so one day, I just opened my closet and looked through all of them.

And wow! I had to google some of the medical terms, but I realized my brain was messed up. It’s crazy that I’m even able to share this story today because of how bad it was, and I’m grateful to God that I’m able to do so. There’s scar tissue from the fever, and if you look at the hemispheres of my brain, the left side is smaller than my right side. Everything is just kind of lopsided.

That started to explain some things, like why I walked funny going through puberty, or why I was so clumsy and dizzy at times.

When I got to college, I went on a journey to find ways to advocate for meningitis and invisible disabilities. I studied the brain, better understanding my own brain, and meeting other people who had seizures.

How Advocacy Changed My Life After Meningitis and Epilepsy

As I was going through my self-discovery, Cameron Boyce, who I watched on Disney Channel as a kid, died in 2019. And it came out that he died of a SUDEP, or sudden death related to epilepsy. I had never heard of that before. It’s a condition that’s rare and usually is thought to happen in people who don’t take medication.

All this time, I wasn’t on medication because one of my parents didn’t believe I needed it. ‘God’s going to heal you,’ and all that.

When the Cameron Boyce Foundation was founded in August of that year, I wanted to help them. I eventually got in touch with Cameron’s mom, Libby. Meeting with her, his dad, and his sister Maya helped me cope with things and definitely molded who I am today. I also met other epileptics, heard other people’s stories, and learned that epilepsy isn’t a death sentence. Today, I’m the community advisory chairwoman for the Cameron Boyce Foundation.

Everyday Life with Invisible Disabilities Like Epilepsy

Sometimes I think about how my life would be different if I’d never had meningitis.

I try not to because you kind of get into a ‘woe is me’ state of mind. But my mom said I was super smart before getting pneumococcal meningitis, hitting milestones really early, so I wonder if school would’ve been a breeze. Would I have gone straight to college instead of taking a 7-year gap after high school? Right now, as a neuroscience student, if I didn’t have to take seizure meds and my memory didn’t suck, would I have straight As instead of settling for Bs or Cs? Who knows.

I told my doctor that I hated the side effects of the medication. It affects my memory and makes me feel tired. He told me, “Well, it’s either the side effects or the seizures.” And we don’t want that.

There are other noticeable aftereffects of meningitis. I can’t drive because my spatial awareness is off. I have 20/20 vision, but my brain just perceives things differently. Just to go to Target or to get McDonald’s or something, I have to wait for my husband to get home.

I get fatigued. It’s like being pregnant. When I was pregnant, I’d just get these bursts of fatigue and need to take a nap. And that’s pretty much every day with me. I’m very grateful that I have a husband who understands. But there have been times when I had to cancel just going out with my friends because I’m tired or feeling dizzy, and I don’t want to take any chances of something happening when I go out.

Now that there’s a pneumococcal vaccine, I’d say, please go get it. If you get the disease, you may not live. And even if you do, it’s a long road ahead. I still don’t know where I contracted it, but my parents made sure my sister had the vaccine, and I made sure my daughter got that vaccine, too.

Monique Hopgood-Willis is a fighter who refuses to let adversity define her. After surviving bacterial meningitis that resulted in epilepsy and cognitive impairments, she continues to live life to the fullest as a dedicated wife, loving mother, and passionate neuroscience (graduate) student. She is committed to helping others be educated about neurological diseases.

Her story, like all others on this blog, was a voluntary submission. If you want to help make a difference, submit your own post by emailing us through our contact form. We depend on real people like you sharing experience to protect others from misinformation.