by Mallory Harris

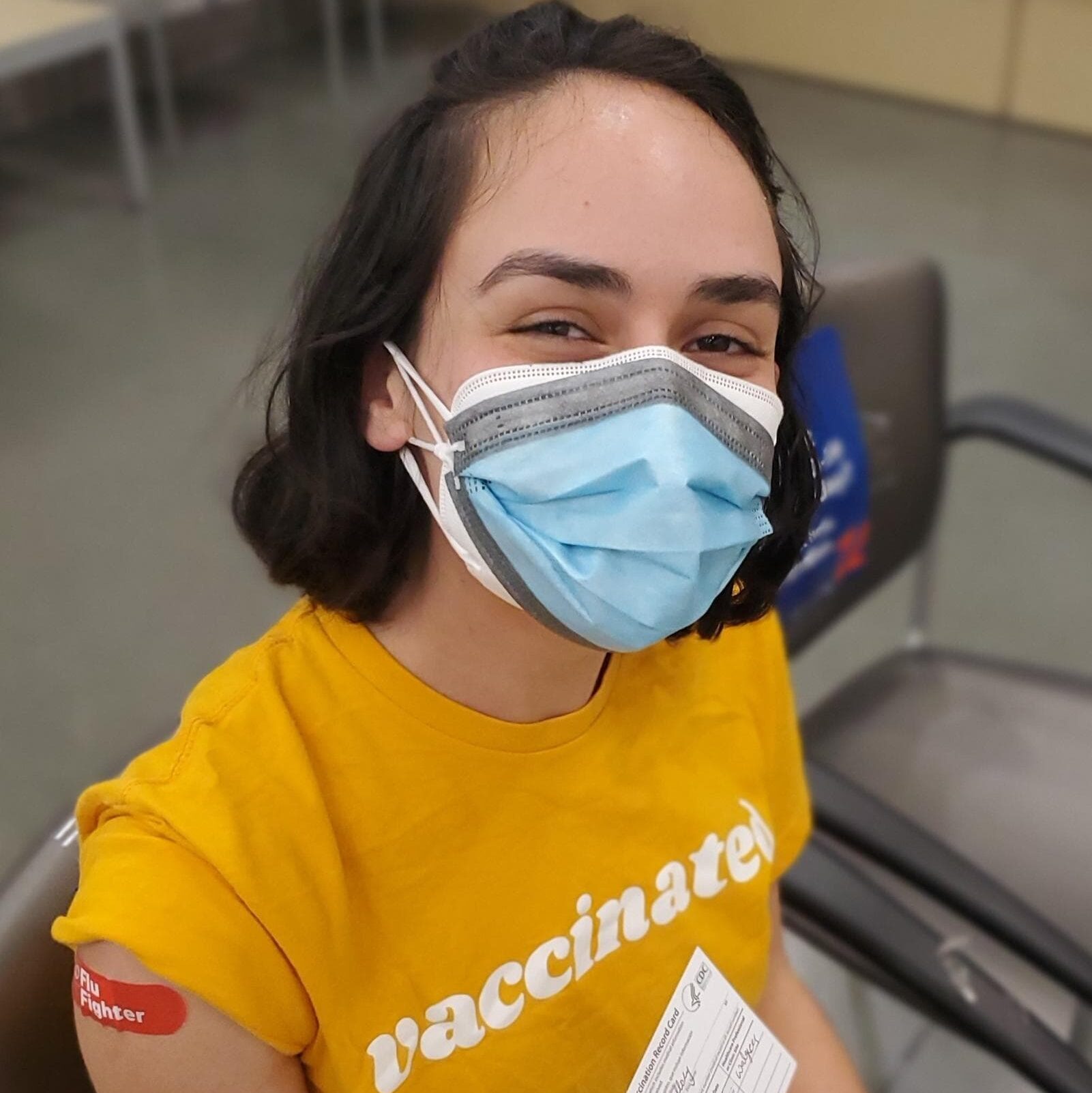

I showed up to graduate school orientation wearing a new, bright yellow shirt declaring me VACCINATED. Having just moved across the country, I was at the starting line of a five(ish) year program studying infectious diseases at Stanford, but I felt prepared.

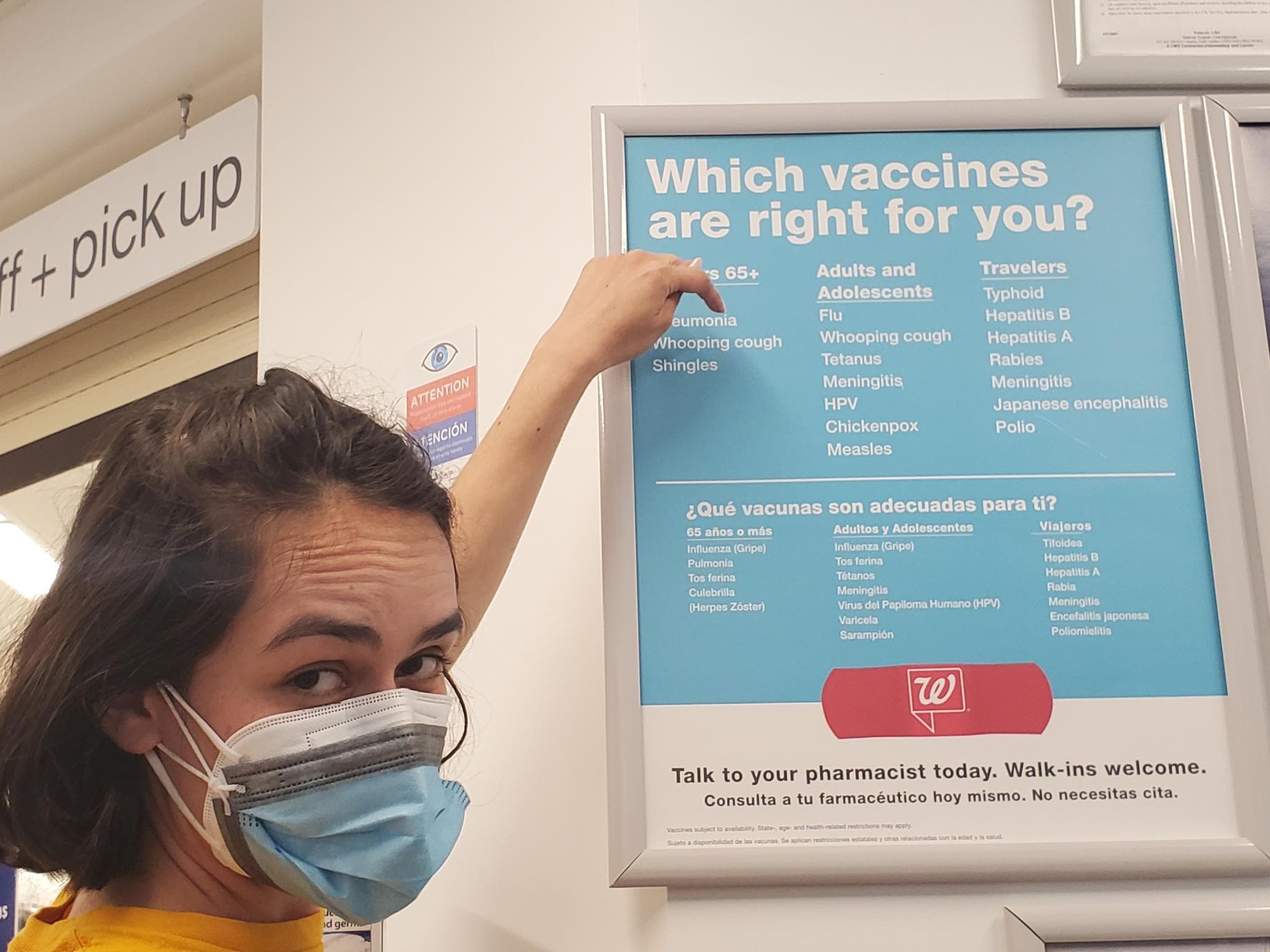

Two weeks later, I woke up in the middle of the night, coughing nonstop for several minutes straight. I skipped my first Friday of class for a walk-in doctor’s appointment and demanded to be tested for the whooping cough. The doctor was reluctant to test me, since I was up to date on my relevant boosters.

It’s unlikely, but I knew I could get whooping cough even though I had been vaccinated. Immunity is good but not perfect and begins to wane a few years after vaccination. Every year, there are tens of thousands of cases of whooping cough in the United States. I say this not to be alarmist. You probably won’t get whooping cough or any other rare infectious disease. If you do, it can be extremely scary and serious.

I had a comparatively mild case, in part due to the remaining protection I had from vaccination. Even so, I sprained a muscle on my side from coughing so hard. I was grateful that I didn’t break a rib, a potential side effect of this disease that can lead to a collapsed lung or lacerated kidney. I went weeks without a full night’s sleep. Every time I started to doze off, I would wake up suddenly, gasping for air. I coughed and coughed and coughed, sometimes until I threw up. I coughed until my lungs were empty and then desperately tried to pull air in through my swollen and sore airways. The damage wreaked by the bacterium and its toxins on my lungs persisted for months, long after I completed a course of antibiotics. There’s a reason this used to be called the “100 day cough.”

But the groups at highest risk of severe complications from whooping cough are babies and young children. Half of babies who get whooping cough have to be hospitalized. The intensity of the cough can make their eyes bleed or trigger a seizure. One out of every two hundred babies who catch the whooping cough will die. Since their lungs are too small to whoop, they simply stop breathing during an attack. When you walk through old cemeteries and see the lines of tiny tombstones, demarcating lifespans of a couple of months? This disease is one of the reasons why.

Whooping cough and many other deadly childhood infectious diseases have become rare in the United States through a combination of vaccines, antibiotics, and incredibly ambitious public health campaigns. With a handful of exceptions, none of my friends have any personal experience with whooping cough, but all of my grandparents had it as children or toddlers.

In an unvaccinated world, whooping cough is one of the most contagious diseases that exists. One infected person can give the disease to over fifteen people, an entire preschool classroom. If those fifteen people all infect fifteen more people, we’re up to 225 new infections.

Cut back to me at orientation, highly contagious but asymptomatic. I snuck out of the session on building a good relationship with your mentor to get lunch with the rest of my lab, my mentor, and her month-old son. Whooping cough is transmitted by coughing or sneezing. It can survive for a few hours on surfaces. I gave my mentor a hug at the beginning of the meal and handed her a hat that my mom knit in the school colors of our shared alma mater. I sat across the table from the fully susceptible baby, but directly next to his mother. He wasn’t old enough to be vaccinated against whooping cough for another month, but his mom recently had gotten the booster, something recommended during each pregnancy that can pass some protection to babies.

You could do a whole montage of my close encounters before I was diagnosed. Me sharing makeup with my sister, a masterful babysitter. Making a smoothie to share with a friend before she spent time with her two young children. Two cross-country flights. Were there passengers on the way to meet a newborn nephew? Spend time with an aging parent in the hospital?

Each of these close calls was a vaccine working as intended, keeping the adults from getting sick but, more importantly, protecting the babies they love. Even the very best vaccine can fail sometimes, which is when we must rely on the immunity of the other vaccinated people around us to hold up and keep a single case from turning into an epidemic. When I go in for my booster or annual flu shot, I’m reducing my personal risk of infection. I’m also shielding my loved ones and protecting a classroom full of my closest friends, their grandparents, and anyone else in their lives who may be vulnerable.

Note: Tdap vaccination guidelines were changed in January 2020 — this could affect you!

Mallory Harrisis a PhD student in biology at Stanford University. Her story, like all others on this blog, was a voluntary submission. If you want to help make a difference, submit your own post by emailing Noah at [email protected]. We depend on real people like you sharing experience to protect others from misinformation.