Common social media "debate" tactics

It’s important to correct false information, whether it’s in a conversation or online. But with social media, the effort can feel daunting because anti-vaxxers use a variety of tactics to frustrate you so they can have the last word. Here are some common social media “debate” tactics and how to address them:

Appeal to emotion

Emotions can often be seen in a logical argument, but often we will see arguments without logic trying to overcome this weakness by making people feel fear, hatred, or revulsion. Acknowledge the emotion but circle back to the facts:

“I understand that hearing such things is frightening. We need to make sure we rely on facts, not emotions. Here are the facts.”

Special pleading (moving the goalposts)

What does a person do when their claim is proven wrong? They claim that their actual claim was different or that there is a special exception for their claim. The goals will keep moving as you prove the other person incorrect.

“I noticed that you have changed the topic. Before we move on, can we please come to some sort of agreement about the earlier topic?”

Burden of proof

Here, a person making a claim will ask you to prove them wrong. But that’s not how it works. If you make the claim, then you’d better bring the proof.

“I know it is frustrating to be doubted, but if you make this claim, you should expect that you will need to provide the facts to support your claim. Please provide your evidence.”

Black-or-white thinking

In this world of thinking, there are only two options. However, truth has many shades. So just because vaccines are not 100% safe, 100% of the time does not mean they are 0% safe. Use common activities to help people better understand risk.

“It’s true, vaccines are not 100% safe, but nothing is. You are more likely to choke to death eating than suffer a serious adverse event from a vaccine. Yet we all still eat. We need to understand the real risk of things to be able to make informed decisions.”

Anecdotal argument

An anecdotal argument is really a study with only one test subject and no peer review. The stories people tell need to be supported by what we know about science, or they should likely be dismissed.

“I appreciate this story is emotional, but we need to rely on facts when making decisions. In this case, the facts do not support that this story could have happened the way it has been told. Here are the facts.”

Texas sharpshooter (cherry-picking)

This logical fallacy starts with a conclusion and then picks the evidence to try to support it.

In science, we look at all the findings and base our conclusions on them. We don’t come up with a conclusion and try to find “evidence” that supports it.

“I noticed that some of your evidence supports your beliefs, but when we look at evidence, we need to consider all of the evidence, not just the pieces we think support our beliefs. When experts look at all the studies and take into account their strengths and weaknesses, their conclusion is very different.

In-group bias

People are often biased toward those they see as part of their group. Accepting arguments from our in-group, without critically evaluating, can lead to incorrect thinking. It’s true that the strongest predictor of whether or not we vaccinate

is the number of people around us who vaccinate.

“I put my trust in experts who, instead, rely on facts and evidence. Here are their conclusions on this topic.”

Belief bias

This bias begins with what you already believe and accepts anything that supports that belief without taking a good, critical look at the evidence.

“Can I ask you to do a thought experiment? If you were arguing the opposite point of view, what would you say to someone?”

Backfire effect

Often, when people are shown evidence that their deeply held beliefs are incorrect, rather than accepting the new evidence, they hold onto their old beliefs even harder. Because of this bias, it’s best to try to help people reach correct conclusions on their own.

“I see that you have done a lot of searching on this topic, and I agree with you on this point. How do you think scientists go from that point to supporting vaccination in this case?”

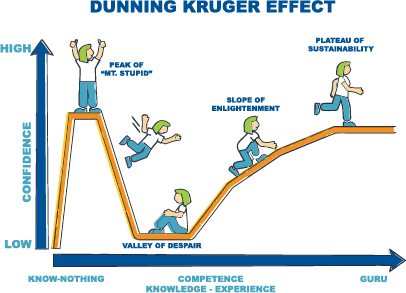

The Dunning-Kruger effect

The more you know, the more you know you don’t know as much as you thought you knew. In other words, people who know very litter are often far more confident in their knowledge than they should be.

“I respect that you have done a lot of reading in this area. Can you respect that the experts have done considerably more study and research and I trust their statements over yours?”

Gish Gallop

In this argument, someone will throw everything and the kitchen sink and the neighbor’s sink at you. It’s a list of arguments so long that you would have no way of addressing them all. So don’t. Ask the person to focus on one argument and discuss that.

“I see that you have laid out more points that I could reasonably answer at this time. What is your one biggest concern that you’d like to discuss with me?”

False Balance

This fallacy gives equal weight to the opinions of experts and complete amateurs. Most often seen in journalism, it gives equal time and weight to two people whose knowledge is not at all equal. Similarly, it might also overemphasize an opinion held by a teeny, tiny minority of people.

“It’s important that we not give equal weight to an expert and a non-expert as though science were a matter of debate. Please stick to the facts and do not give voice to non-expert extremists.”

The shill gambit

This argument assumes that the opponent is only making their arguments because they are paid to do so.

“This conversation is not about employment or personalities, but about facts and evidence. Let’s please return to discussing those.”

Just Asking Questions

This tactic works to instill uncertainty by asking a lot of troubling questions. A person using this tactic is not looking for answers, but trying to make people feel doubtful about what they thought they knew.

“It sounds as though you have many questions. Which of these questions is the most important to you? Can you tell me more about why that question concerns you?”

Appeal to nature

This fallacy assumes that what is natural is best, even though all sorts of natural things try to kill us.

“I understand that it is comforting to rely on nature over science, but the truth of the matter is that vaccination is a combination of both. Vaccines are a way for our natural immune system to be trained to fight what is dangerous in nature.”

Appeal to conspiracy theory

This fallacy relies on people’s sense of powerlessness by reinforcing the idea that a nefarious group is out to get them. It’s notable that large conspiracies are always outed fairly quickly. See: Watergate.

“I understand why you distrust official sources, including governments all over the world, universities and non-government organizations.”

A word of warning, there very often is no reaching someone who is so far down the conspiracy rabbit hole. They will switch from one tactic to the next as you quash them. You need to decide if you want to engage in what could become a “whack-a-mole” online debate or report disinformation.

Some guidance if you do want to engage

Be polite…to a point.

- If someone is bullying, it’s okay to call them out and to report them on social media.

- If someone is offensive, you should call them on it. Some anti-vaxxers have equated some pro-vaccine people to Nazis. If something like this them know in no uncertain terms that equating genocide and vaccines is insensitive to victims of the Holocust, ill-informed, and outrageous.

Use we, not me or I.

Generally speaking, regardless of what you’re talking about or who you’re talking to (business associates, friends, or online) this approach is better. It’s more inclusive, assumes buy-in on certain things, and doesn’t seem like you are presuming you are the end all, be all. We don’t have to agree but let’s agree to keep this polite. We all want what’s best for our children…

Don’t escalate, don’t engage.

Regardless of what someone says, don’t sink to their level. Call them on their behavior (politely) and disengage.

Know when enough is enough.

After five back-and-forths without making any progress, it’s time to bow out. Prolonging the conversation may ultimately be harmful as it provides more opportunities for the sharing of misinformation.

Let people know you are done.

Oftentimes if you just disengage, the person will say, “see, they had no come back so they left. Just shows you I’m right.” So before you disengage, say so. “This isn’t productive so I’m not continuing this conversation any longer, but if

you do want credible information in the future, please let me know.

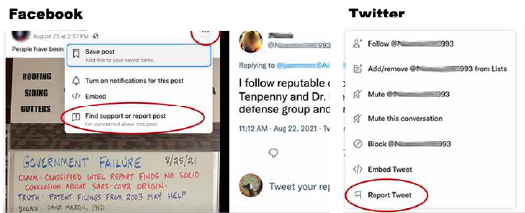

Report mis-, dis-, and malinformation.

Studies show that Facebook has a great amount of mis-, dis, and malinformation but all social media is susceptible. And all platforms have the ability for you to report it. The only way we are going to get a handle on false information is to report it when you see it.

Look for the 3 dots in the upper right or report post” or “report tweet” depending upon if you are using Facebook or Twitter.

Links to report mis-, dis-, and malinformation on social media

- How to report false information or abuse on Facebook.

- How to report false information or abuse on X (formerly known as Twitter).

- How to report false information or abuse on TikTok.

- How to report false information or abuse on YouTube.

It’s ok, to disengage politely saying, “I’m sorry you’re not in a place to learn the facts. But if things change in the future and you want credible information, please know I am here for you.” And leave it at that.

© Voices for Vaccines. Excerpts and links may be used by websites and blogs, provided that full and clear credit is given to Voices for Vaccines, with appropriate and specific direction and links to the original content. Parents, providers, advocates, and others may download and duplicate toolkits in print, without alteration, for non-commercial use and with full and proper attribution only.