By Patricia Walters-Fischer, RN

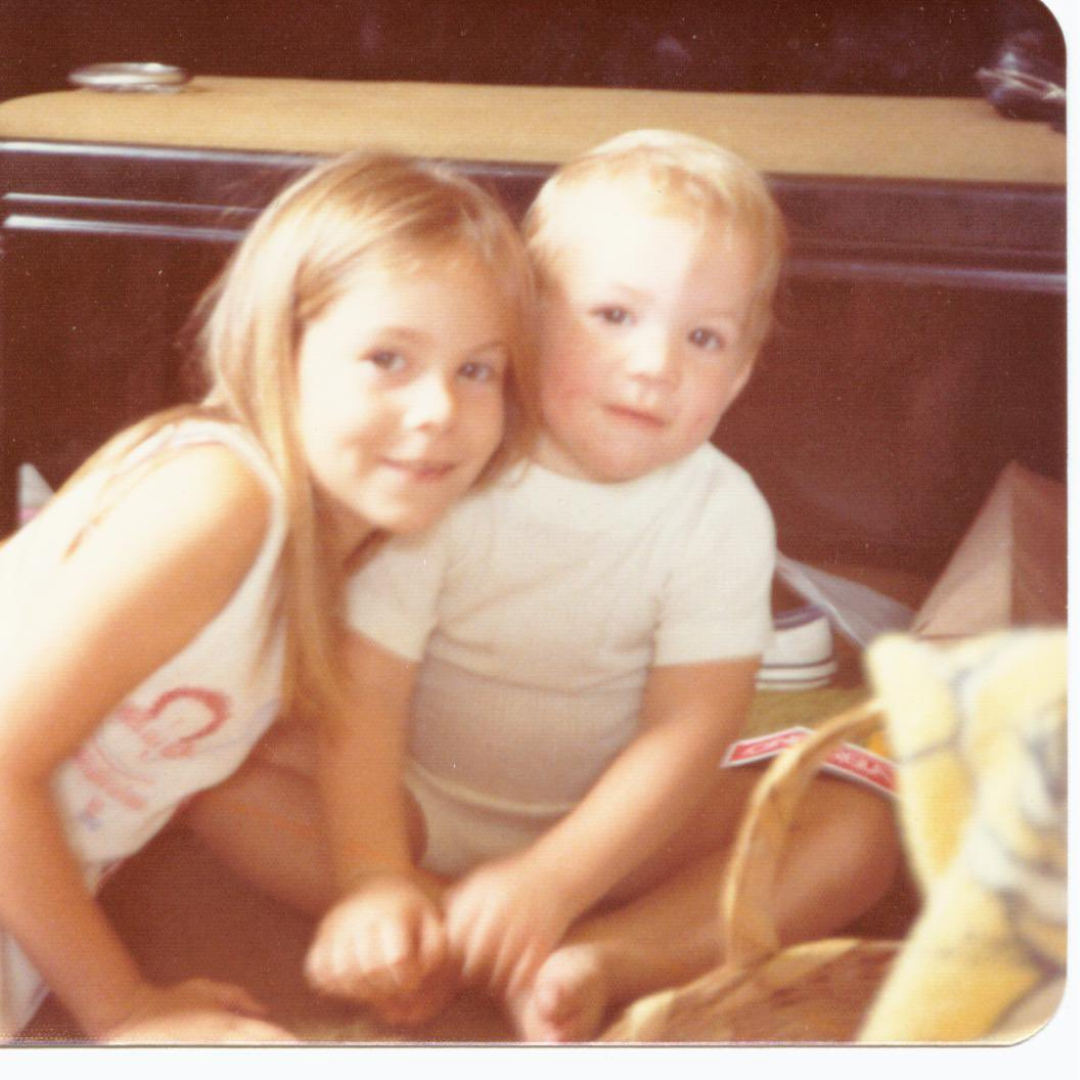

Waaaaaaay back in May of 1973, I looked forward to my last day of kindergarten. I remember my teacher a few of my classmates, and that I had a cute baby brother at home that I got to spend the summer with.

Within a few days of our year-end celebrations, I started feeling sick. Fever, chills, malaise, and these itchy spots on my chest and belly.

I had a raging case of the varicella-zoster virus, or what is more commonly known as chickenpox.

A Benign Childhood Disease?

It was awesome to be able to spend the first couple of weeks of my (hot) Texas summer vacation sick. Of course, my brother got it worse after me. In fact, the entire class got it since someone decided to send their very sick kid to school on the last day because “he’d miss his friends” if he didn’t get to go.

The level of fury by parents that summer probably simmered below volcanic. Summer plans had to be canceled, work schedules and daycares rearranged, and kids had to be quarantined from adults who never had the virus.

My best friend, Elizabeth and I broke out within hours of each other. Our younger brothers followed a few days later, and both of our mothers were mental by the end of June.

Chickenpox was almost a rite of passage when I grew up. You get sick, have to stay home, have lifetime immunity. No biggie, right?

So when I became a nurse in the early nineties, my approach to chickenpox was the same. It’s no big deal. Inconvenient, uncomfortable, itchy, and frustrating, but no big deal. When the vaccine came out, I eyerolled because chickenpox was NO BIG DEAL.

Everything changed when I worked as a triage nurse at a Level 1 children’s hospital in Dallas, where I discovered why it was a very big deal.

Treating Chickenpox in the Hospital

A three-year-old came in with a fever over 103°, miserable, and covered in chickenpox pustules. Lifting his shirt for the exam, I saw the poor boy had a golf ball-sized abscess on his belly, due to scratching. Natural bacteria on the skin and whatever he had under his nails set up the perfect environment for that infection to flourish. The mom reported that it basically popped up overnight, and she brought him right in.

Scratching at chickenpox spots is nearly impossible to avoid, especially with a toddler.

Because of that massive abscess, he was immediately admitted for a five-to-seven-day hospital stay and placed in isolation. That afternoon, he underwent surgery to debulk and clean out the abscess. We hoped he only needed one surgery.

Of course, he was given IV hydration and heavy antibiotics.

Being in the hospital when I was eight for appendicitis, I remembered how scary it could all be. Staying in a foreign place with weird smells and people I didn’t know coming in and out of your room day and night. All of it could easily terrify any child.

For him, doctors and nurses wore masks, so he couldn’t totally see their faces. He had no freedom to walk outside his room without protective equipment (many hospitals wouldn’t let kids leave at all). Any close family members who never had the disease, he could not see.

Once his treatment was explained to me, I realized how arrogant I’d been about varicella. Just because my brother and I got through that miserable summer without issues doesn’t mean other kids did.

Chickenpox Can Be Life-Threatening

I talked to other nurses and residents and they all had similar stories about kids coming in with infected chickenpox lesions.

And worse.

One terribly sad case was a grandmother with active shingles lesions on her face. She kissed her newborn grandson on his scalp, near the insertion site of the internal fetal electrode he had placed, and he ended up in the ICU with encephalopathy. (People who’ve had chickenpox as kids have a high incidence of developing shingles as an adult.)

Skin infections and scarring weren’t the only concerns. Septicemia, toxic shock syndrome, flesh-eating bacteria, encephalitis, and bacterial pneumonia are possible severe complications.

And kids died from this seemingly “rite of passage” childhood disease.

Even with the best surgeon, that three-year-old would have a large scarred crater on his belly where that abscess ate his flesh. And this kid only had one wound. Think of those who had multiple. The large, permanent scars on their bodies, their faces. How they’d have to explain it when anyone asked.

Why We Vaccinate Against Chickenpox

The idea of it all made me reevaluate my opinion not only of that disease but vaccines in general.

I started talking to specialists, reading reliable articles and books, and paying more attention. The more knowledgeable I became, the more I realized that this rite of passage of childhood isn’t something to be minimized.

I spoke to my parents about it, and they said if the vaccine had been available when we were kids, we all would have gotten it.

Before the chickenpox vaccine was introduced in 1995, over 4 million people in the US were diagnosed with chickenpox, with 10,500-13,000 hospitalized and 100-150 dying.

Once the US chickenpox vaccination program was introduced, it’s estimated that it’s prevented 91 million cases of the disease along with 238,000 hospitalizations, and 2,000 deaths.

According to the CDC, today, there are fewer than 150,000 cases of chickenpox, fewer than 1,400 hospitalizations, and less than 30 deaths due to the disease. (And although those death numbers might not seem like a big deal, they are when it’s your family.)

As miserable as that kid was that day, I will never forget him. Not only because of his condition, but how he got me to open my eyes a little wider, learn a little more, and ground my ego.

Patricia Walters-Fischer RN, is a health journalist, best-selling author, podcaster, and mother of four. During her nursing career she worked pediatric and adult critical care/trauma. Her story, like all others on this blog, was a voluntary submission. If you want to help make a difference, submit your own post by emailing us through our contact form. We depend on real people like you sharing experience to protect others from misinformation.